By Sarah E. Needleman

When Electronic Arts Inc. revamped its soccer videogame to let

people control a fictional player's life off the pitch, developers

didn't write new code from scratch. They borrowed it from a game

with dragons.

The feat was possible because EA spent a decade investing in

versatile code called a game engine. Now such software is drawing

attention from Silicon Valley investors and companies such as

Facebook Inc. and Amazon.com Inc.

Engines, much like their namesake car part, are the dynamic

workhorses that make videogames tick. They have grown sophisticated

enough to handle core duties such as graphics and physics for a

company's entire pallet of games, saving time and money on

development.

Years ago, plucking code from one game to use in another

"would've taken us three times the effort," said Patrick Söderlund,

executive vice president at EA Worldwide Studios, a division with

more than 3,000 developers. That is because the company used to

rely on more than a dozen different engines to make computer and

console games. Now it uses just one: "Frostbite."

"If we can get more efficient and reduce friction, it gives us

economies of scale," Mr. Söderlund said. EA's "FIFA 17," which came

out last week in the U.S., is the most important game yet in the

company's arsenal to deploy Frostbite.

The bottom-line benefits are difficult to quantify. Industry

executives, though, say they trickle throughout all aspects of

development, providing everyone from artists and designers to

programmers and audio engineers easy access to the different tools

they need to build games for a broad range of platforms.

Facebook thinks a widely used game engine will help revive its

dormant videogame business, which generated peak revenue of $65

million in December 2011, according to Piper Jaffray Co. analysis.

Today, the social network is churning $45 million a month from

games, accounting for roughly 3% of its total revenue, the bank

said.

In August, Facebook announced a partnership with Unity

Technologies Inc., whose engine powers the blockbuster mobile app

"Pokémon Go." The social-networking company wants game makers that

license Unity's engine to be able to convert their wares for

Facebook's site with just a few clicks, rather than have to rebuild

them from the ground up.

"It was important to partner with Unity because they have an

engine used by so many developers," said Leo Olebe, director of

global games partnerships at Facebook.

In making it easier for developers to bring games to the

company's site, Facebook is hoping to capture a slice of the

growing videogame market, which is on track this year to reach

$99.58 billion in annual global revenue and $118.63 billion by

2019, according to research firm Newzoo BV.

Unity raised $181 million in July in a round led by venture firm

DFJ Growth, valuing the company at $1.5 billion and bringing its

total funding to date to $206.5 million.

Game engines like Unity are hot because they make it easier for

developers "to put out more and better titles faster," which can

boost revenues, said Barry Schuler, a partner at DFJ. They also

give developers access to growth areas such as mobile, augmented

reality and virtual reality.

For example, Facebook's Oculus unit last Wednesday pledged to

cover a portion of licensing fees for developers who use an engine

called "Unreal" from Epic Games Inc. to create content for its Rift

virtual-reality goggles.

Amazon.com Inc. also has been building out its ambitions in

gaming with its live-streaming site Twitch and Fire TV set-top

box.

In February, the company introduced a free engine called

Lumberyard, with the expectation many users will opt to host games

they create with it on Amazon's paid cloud service, said Michael

Frazzini, vice president of Amazon Games.

The company's own game studio last week released its first three

titles made with Lumberyard. The computer games were designed for

both playing and watching on Twitch, which is the third-largest

source of U.S. internet traffic, trailing only Netflix and YouTube,

according to network researcher DeepField Inc.

Psyonix Inc. uses Epic Games's Unreal engine, which charges an

average royalty of 5% of sales. With Unreal, Psyonix developers

were able to make cars from their hit soccer-racing mashup "Rocket

League" glide along stadium walls and fly through the air -- no

complicated math required.

"I didn't get into games because I wanted to create a better way

to develop graphics," said Dave Hagewood, chief executive of

Psyonix, a 60-person company. "I wanted to create gameplay, design

rules and characters." He declined to say how much Psyonix spends

licensing Unreal.

EA's gambit a decade ago to make all its console and PC games

with one engine failed.

Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter estimates by using

Frostbite alone, EA could save about $20 million a year.

Money isn't the only gain, Mr. Söderlund said. He stressed the

intangible gains, such allowing EA's different studios across the

globe to more easily collaborate, as they did by using code from

"Dragon Age: Inquisition" in "FIFA 17."

"We'll see a lot more of that going forward," Mr. Söderlund

said.

Write to Sarah E. Needleman at sarah.needleman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 10, 2016 14:32 ET (18:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

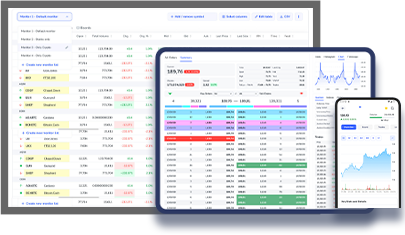

Electronic Arts Inc. (MM) (NASDAQ:ERTS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

Electronic Arts Inc. (MM) (NASDAQ:ERTS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024