By Carolyn Cui and Serena Ng

A new power in sugar trading is buying unprecedented amounts of

the sweetener on the U.S. futures exchange, creating confusion in

one of the world's most volatile commodity markets.

The power is Wilmar International Ltd., a Singapore-based

agribusiness whose major shareholders include the family of

Malaysian billionaire Robert Kuok and Chicago-based Archer Daniels

Midland Co. Wilmar, founded 26 years ago, is one of the world's

largest palm-oil producers but a relative newcomer in the sugar

business.

Last week, Wilmar agreed to buy $512 million in raw sugar at the

expiration of a popular futures contract on the ICE Futures U.S.

exchange.

Wilmar has been scooping up sugar by physically settling tens of

thousands of futures contracts and collecting the commodity from

ports across South America and elsewhere. The company has bought

more than 6 million tons of sugar in this manner since 2015, enough

to fill roughly 3,000 Olympic-size swimming pools at a cost of some

$2.3 billion.

The effects of Wilmar's moves have been the subject of debate

among traders. At one point in 2015, when sugar prices were at

multiyear lows because of a world-wide glut, Wilmar bought so much

that traders say the company in effect mopped up that year's global

oversupply. In the rally that followed, sugar prices more than

doubled.

Then, as prices peaked in September last year, Wilmar changed

course and delivered excess sugar it owned to other traders on the

exchange. Sugar prices fell 24% in the ensuing months.

"Everybody was looking at them," said Bruno Lima, head of sugar

and ethanol at brokerage INTL FCStone in Brazil. Last week, traders

and analysts ruminated on Wilmar's latest purchase and whether it

was a positive sign for sugar demand. Prices have edged higher

since.

Wilmar, which entered the sugar business in 2010, owns sugar

cane plantations, mills and refineries mostly in Asia. It also

trades sugar, buying raw sugar and selling it to refineries all

over the world. Last year, the company handled 13.5 million tons of

sugar, representing roughly 8% of the world's production. Some

analysts say Wilmar is now possibly the world's biggest sugar

trader.

The company's size and scale, however, are sowing concerns among

some traders that it could control a large amount of the world's

tradable sugar and influence prices.

"They are a market mover," Nick Gentile, head trader of New York

commodities trading firm Nickjen Capital, said of Wilmar. Around

two-thirds of the world's sugar production is consumed in the

countries that produce it, and the rest is traded

internationally.

Jean-Luc Bohbot, the 48-year-old Frenchman who runs Wilmar's

sugar business, said there is no evidence that the company's trades

affect market prices. That is "very much an incorrect view," he

said in a recent interview. "Sugar is an extremely fragmented

commodity, with a very large number of players around the

globe."

While Wilmar's sugar purchases and sales appear in some cases to

have preceded rising and falling prices, Mr. Bohbot said, "There is

no clear correlation" between the two. Over the past few decades,

sugar prices have gone in both directions when there were large

physical deliveries, he added.

Many producers, end-users and speculators use commodity futures

contracts to hedge price risks or make directional bets on prices.

Futures are often used as a guide for pricing in the physical

markets where actual commodities are exchanged.

Physical settlements of futures trades, however, are rare.

Exchange operator Intercontinental Exchange Inc. estimates that

fewer than 0.5% of trades result in the actual delivery of

commodities. The vast majority of futures contracts are unwound by

traders before they expire because most firms want to avoid the

hassle of transporting commodities to or from inconvenient

locations. With sugar futures, buyers don't know where in the world

they will have to pick up the sweetener until after the contracts

expire.

That hasn't deterred Wilmar. Mr. Bohbot said the company has

found it economical to purchase sugar in bulk using futures

contracts, because the exchange's rules require sellers to deliver

the sugar on board buyers' ships, which facilitates international

trading. In other commodity markets, such as grains or metals, the

handover usually happens inside warehouses in locations that often

might not be easily accessible.

Mr. Bohbot said Wilmar ships and sells most of the raw sugar it

buys to refineries in Asia and the Middle East, where consumption

is growing. This sort of trading, however, is often barely

profitable when shipping and other costs are factored in, he said,

noting, "There is very little margin, and sometimes no margin."

In 2016, Wilmar's sugar division posted a 33% year-over-year

increase in revenue to $5.9 billion, "an outstanding set of

results," according to the company, partly because of higher sugar

prices. It earned $125 million from the sugar business last year,

for a profit margin of 2.1%.

Wilmar entered the sugar market through a $1.5 billion takeover

of Australia's largest sugar producer. then hired Mr. Bohbot, who

has a long career in sugar trading, from a rival and tasked him

with expanding the sugar business internationally. Wilmar made many

acquisitions and entered into joint ventures with sugar producers

and refineries in countries including Indonesia, Myanmar, India and

Morocco. Last year the company formed a new venture with a major

Brazilian sugar producer -- a move likely to increase the volume of

sugar it handles.

Frank Jenkins, president of Jenkins Sugar Group, a trading firm

in Connecticut, said Wilmar's large-scale buying of sugar from the

futures market "is a symptom of the growth of their business."

Write to Carolyn Cui at carolyn.cui@wsj.com and Serena Ng at

serena.ng@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 07, 2017 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

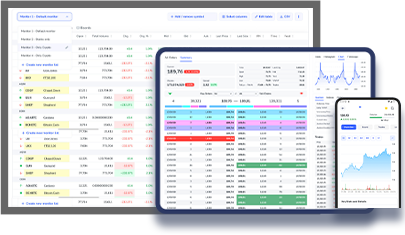

Wilmar (PK) (USOTC:WLMIY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2024 to Dec 2024

Wilmar (PK) (USOTC:WLMIY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2023 to Dec 2024